The Poor Posture Epidemic Meets the covid-19 Pandemic

The covid-19 pandemic is severely testing our society. Those who remain healthy and employed — and can work from home — are lucky indeed. However, growing numbers of these fortunate people suffer from needless pain, strain and tension induced by their own poor posture.

Poor posture was already at epidemic levels before the pandemic began. Yet covid-19 “shelter-in-place” orders have amplified our society’s preexisting posture problems. Many office workers have been confined to small spaces filled with furniture that has little to do with offices or work. The poor design of this furniture from a functional standpoint is only encouraging harmful postural habits. These habits, in turn, are amplifying the physical and psychological pain of the pandemic – and they will cause preventable health problems long after the pandemic itself has been brought under control.

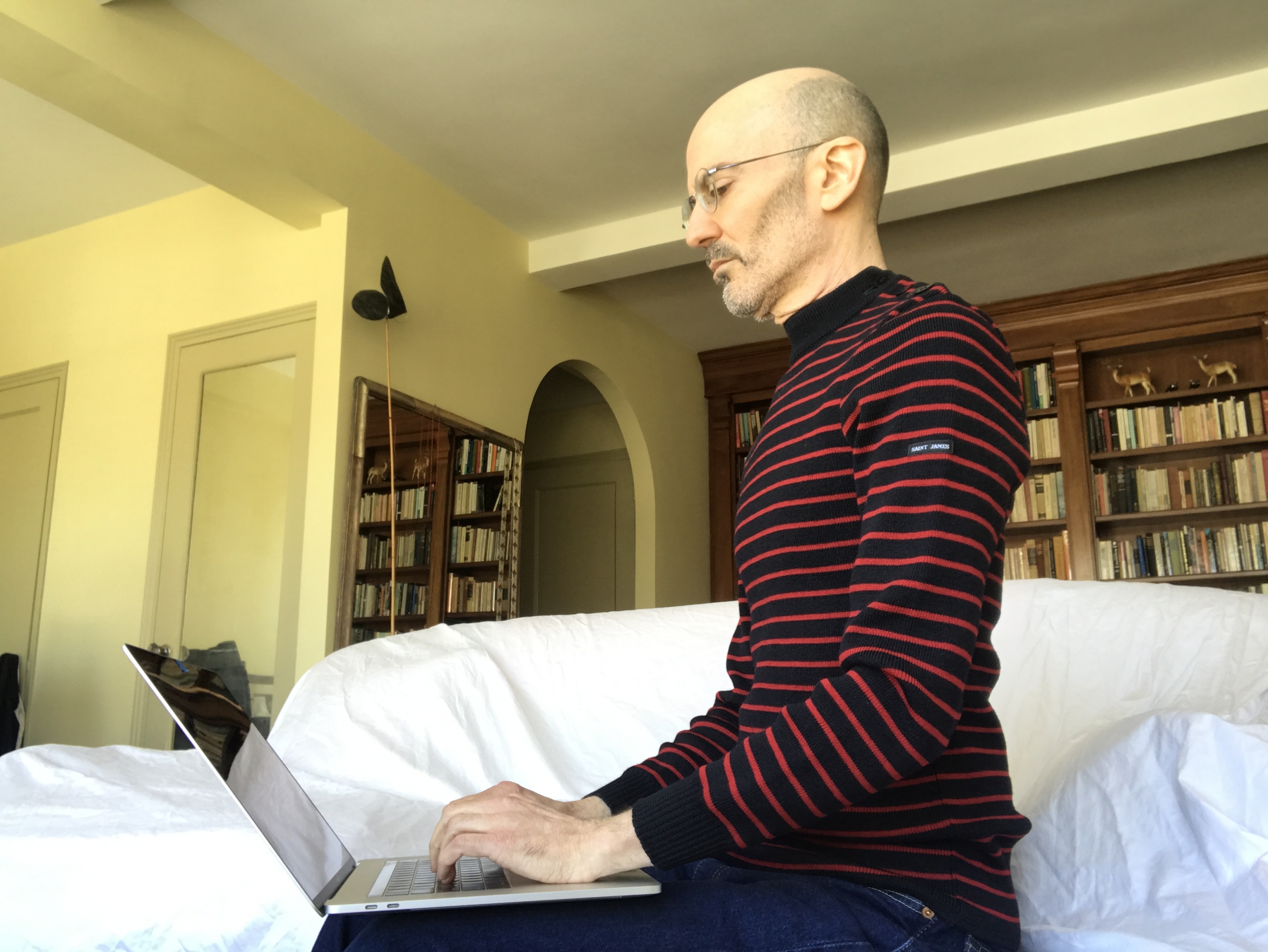

Stuck at home, slumping… there has to be a better way!

Posture Help is Elusive and Often Illusory

Many office workers stoically endure their back, neck and shoulder pain, mistakenly believing that it is unavoidable or transient. Others seek help to reduce their pain, only to find inaccurate or contradictory information. A recent article in the Washington Post offers positive and negative examples of the posture “tips” awaiting back pain sufferers online. Let’s look at the article and discuss its problematic assumptions and advice.

The Pitfalls of Mindless Repetition

The Post’s article quotes several noted experts in relevant fields. Among these is Jon Cinkay, body mechanics coordinator at New York’s famed Hospital for Special Surgery. Cinkay advises us to organize our work environment as follows:

“’You’ll want to adjust your chair so that elbows sit at a 90-degree angle; where your hands end up is where your keyboard should be.’… Thighs should be parallel to the floor and feet should sit flat. If they dangle even a little, put a box or some books on the floor to support them.”

This sensible advice reflects textbook ergonomics. And it is consistent with the nearby diagram, published in an IBM “Ergonomics Handbook” during the early 1980s. Cinkay and countless others have sung the same song over and over again for decades, to no avail. Despite all their well-meaning advice, millions still suffer from avoidable back, neck and shoulder pain. Why? Because people don’t do – or don’t know how to do – what they’re being told here.

It’s pointless to repeat information so widely available – and so widely ignored – for so long. We need to understand why so many people continue to go wrong in their sitting, standing and walking. Together with this understanding, we need to deploy a different method to help people address their own posture problems. Spoiler alert: that method is the Alexander Technique.

Human Habits Defy Ergonomics

The basic problem is that any environment, no matter how well designed, is only as effective as the people relying upon it. And the effectiveness of people in this context depends on their ability to read, understand and execute instructions. Unfortunately, even the most basic instructions can be not read, misread, or misunderstood. It is fairly common for one person to commit all of these errors when looking at a set of instructions.

As for executing instructions, the problem there becomes even thornier. Even if someone reads instructions carefully, they can still fail to do what they are told to do. Failure is especially likely if the instructions contradict longstanding habits that people don’t even realize they have. Postural habits are exactly these sorts of habits.

Advice Falling on Deaf Ears

Let’s carefully examine the collision of “correct” advice with deeply engrained postural habits. Here’s more seemingly sensible advice, courtesy of the WaPo article:

“To make sure your lower back is supported while you work, sit back in the chair so it’s cradling your spine all the way up to your shoulder blades. If your chair lacks lumbar support, roll up a towel and nestle it between the small of your back and the chair.”

Advising people to sit back in their chairs to get support is technically valid, but it will usually fail for two reasons. First, poor chair design virtually guarantees that someone sitting “back in the chair” won’t get adequate low-back support. Usually, a rolled-up towel won’t address this problem. Second, it’s easy to misunderstand the phrase “sit back in the chair.” In fact, many people will modify the instruction to accord with their pre-existing habits without even realizing it.

Most people plant themselves in the middle of the chair seat and then slump until their back is partially supported. As the illustration shows, the middle of the back gets support, while the low back remains rounded, compressed and unsupported. This happens without any conscious awareness on the person’s part – he just slumps habitually. This slumping is a leading cause of needless and avoidable back pain among office workers.

People who sit slumped in the middle of the chair seat don’t know what sitting “back in the chair” means. Many will read this instruction and think, “I’m not sitting in the front of the chair, so I must already be sitting in the back.” For the vast majority of readers, the instruction is far too vague. For the Alexander Technique student, it is too specific.

How The Alexander Technique Can Help

The Alexander Technique leaps past the whole problem of telling people how to sit. Alexander teachers avoid giving students detailed instructions that are easy to forget, ignore or misinterpret. Instead, they teach students how to think while they pursue ordinary daily activities.

How should people think while sitting? In Alexander practice, a student thinks about sitting in much the same way she thinks about standing, walking, running, etc. This thinking starts with students avoiding habits that cause pain, such as slumping in the low back or pulling the neck forward and the head down. Students usually manifest the same habits in multiple activities. That is, the habits are person-specific, rather than being specific to any particular activity. The Alexander Technique student learns to think, “I tend to do X when I sit, stand and walk. X makes my back hurt, so I’ll try to avoid doing X.”

The Alexander Technique makes sitting easy and comfortable.

While the student avoids enacting habits that cause poor posture and trigger pain, she simultaneously thinks of simple directions that promote good posture. These directions are: “I wish to allow my neck to be free, to allow my head to move forward and up, to allow my back to lengthen and widen, and my knees to go forward and away.” It may seem odd that these directions take the form of wishes. But when we remember how often people misunderstand instructions, framing the directions as wishes makes perfect sense. Wishes are thoughts; there is nothing to do and no pressure to do it correctly. And it is easier to teach someone to avoid incorrect thinking than to teach them how to perform correct “doing.”

Final Words

The thing we call “posture” is the complex, subtle and intimate expression of each person’s whole body and mind. If “good posture” could be reduced to a set of instructions, then back pain wouldn’t be both common and also increasingly prevalent in the world today. The traditional approach taken by the Washington Post article has failed too often to have any real credibility. We need a radically different approach to the intractable challenge of preventing back, neck and shoulder pain. We need the Alexander Technique.

For 125 years, the Alexander Technique’s focus on inhibiting harmful habits and promoting positive directional thinking has benefited countless students. With diligence, attention and patience, those benefits can be yours as well. Having read this far, why don’t you give it a try?

Leave A Comment