I'm currently re-reading Dr. Oliver Sacks's famous book "The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat." Chapter 3, "The Disembodied Lady," tells the fascinating tale of a woman who lost her ability to sense her own body. Christina went overnight from a state of vigorous health and youthful activity to one in which she could not function at all. Without her 6th sense (her proprioception as Charles Sherrington named it in the 1890s), Christina could not even sit up in bed. She eventually regained a tiny fraction of her abilities by using her eyes to continually confirm the existence of her own body.

Our vital – and tenuous – body-mind connection

Imagine if you were to wake up one day convinced that your arms and legs were not yours at all. How would you use your arms and legs in this situation? Even the "simple" act of putting a glass of water to your own lips would become nearly impossible.

Fortunately, you and I do not suffer from a severe neurological deficit like that of Christina. We can lift a glass of water to take a drink, or walk to a nearby store if we prefer a different beverage. But that does not mean we have nothing to learn from Christina's catastrophe. We can investigate just how reliable our sense of ourselves, our own proprioception, actually is. We can ask: What's the quality of my ongoing mind-body connection?

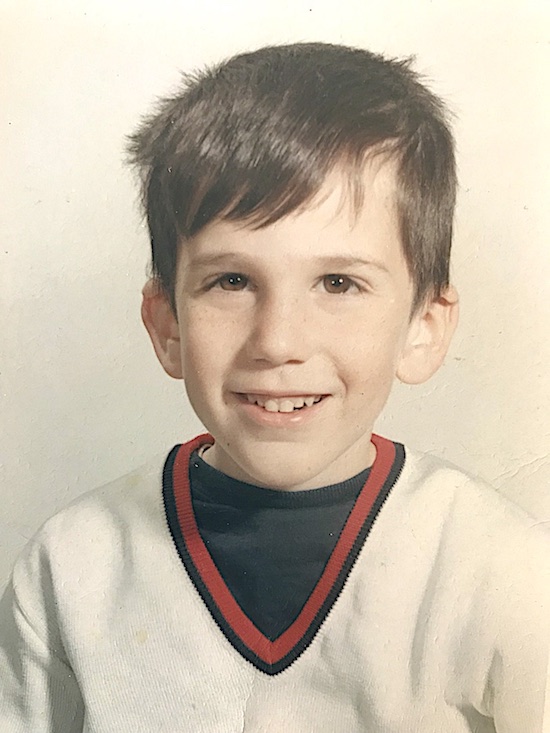

When I was growing up, I was a small and skinny boy. I was convinced that I had poor coordination and thought myself hopeless at anything "physical." In other words, I suffered from a negative body image despite the absence of any actual impairment. Because of my distorted self perception, I didn't do things I actually could (or should) have done. In this way, I was a little like Christina.

When I was growing up, I was a small and skinny boy. I was convinced that I had poor coordination and thought myself hopeless at anything "physical." In other words, I suffered from a negative body image despite the absence of any actual impairment. Because of my distorted self perception, I didn't do things I actually could (or should) have done. In this way, I was a little like Christina.

Body image collides with reality

I had a special problem with team sports, which were enshrined at the center of our young lives. Whenever we formed teams for any game, I was invariably among the last boys to be picked. I endured this humiliating ritual countless times. In baseball, all the outfielders crowded the baselines whenever it was my turn at bat. Then they insolently watched me swing the bat, just in case my flailing attempts ever caused the ball to roll in their direction.

After only one or two games, everyone firmly believed that I could never, ever hit a baseball. This is a testament to how quickly habits are created, and how little it takes for habits to gain mythological strength.

However, I remember one occasion when I unexpectedly connected bat and ball. The ball sailed far up into the air and landed well behind the outfielders, who were completely stunned. While those jerks scrambled madly to recoup the ball, I trotted around the bases and claimed my home run.

Lessons not learned

This unusual event went to waste because I ignored its implications. Had I paid attention, I would have seen that my being "bad at sports" was just a myth. This myth was merely the product of habitual thinking. And the habit came from a cultural bias favoring larger boys over small ones. Thus, my self image was based on a habit, and the habit was based on a cultural bias without any foundation. It was a self-fulfilling prophecy based on nothing at all.

In fact, I was perfectly capable of hitting a baseball. What held me back was not my body, but my attitude about my body. Though young, I was already a slave to my habitual self perception, a self perception that was painfully limiting. I could have transformed my playing if I had changed my attitude and practiced with an open mind. Then I could have changed the whole team sports dynamic that I found so humiliating and oppressive. Unfortunately, though, I didn't change my attitude or practice. I didn't change anything at all.

Painful habits are more comfortable than the unknown

Why didn't I change my attitude or practice to improve my performance? First, habits are difficult to break. Even habits based on painful, flimsy ideas can be incredibly strong. Second, I preferred the myth that I was inferior at sports to the reality that I was merely average. I was so invested in my negative body image that even embarrassment and unpopularity couldn't shake my attachment to it. If I let go of the idea that only intellectual pursuits could save me from an unreliable body, what would become of "me?" I shrank from examining the vital question of my own identity, a question many people turn away from year after year.

The fear I felt as a youngster is widely shared. Our culture eagerly sells us distraction and entertainment as alternatives to self examination. Yet it is exactly in confronting our fear and the myths that lie behind it that we can reconnect our bodies and minds with each other and with reality. As Ralph Waldo Emerson said, "People wish to be settled. Only as far as they are unsettled is there any hope for them."

In Oliver Sacks's "The Disembodied Lady," Christina's identity disappeared because she lost her ability to sense her own body. On the other hand, my own identity was based on the idea that I could not use my body in certain activities. When I stepped up to the plate with a bat, I became my own particular version of Christina.

An actual neurological impairment can impair our ability to function. Or, we can create an impairment just through the strength of our erroneous fixed ideas. The end result can be remarkably similar and equally damaging.

The Alexander Technique can help us curb painful habits

The Alexander Technique can help us curb painful habits

Nowadays, I spend my time challenging myths and misconceptions that hamper my students' coordination and waste their energy. I can succeed as an AT teacher because of the many years I spent grappling with my own self-imposed limitations. In fact, I'm still grappling with my self-imposed limitations even as I write these words.

I have worked with students who claim, just as I used to claim, that they aren't "body people" or "body conscious." Other students look at an activity and feel convinced that they could never do it "that way." Still others receive the same information many times without actually hearing it. They can't register the information because it runs counter to their fixed ideas.

These student responses parallel my own personal experience to an uncanny degree. I consider it a privilege to work carefully and patiently with each student's unique matrix of mirages and misconceptions. We collaborate and experiment, cultivating the right conditions for her to break through her own unique habitual pattern. It can happen in a flash, like a bat hitting a baseball. However long it takes, and however unexpectedly it comes, it's always thrilling. Body and mind have come together at last.

Leave A Comment